Discover more from Do the Work

All those movies you watched in high school MEAN SOMETHING

A few weeks ago, I read my friend Lindsay Eagar's next book, the middle grade The Patron Thief of Bread. (A lucky perk of being friends with other writers is getting to read their books early.) I read for about ten minutes, and realized I was overcome with extreme envy. The Patron Thief of Bread is good. Very good. And there were a few descriptions in particular that walloped me with their excellence, and the result, I'm embarrassed to say, was egotistical sadness. I was at the tail end of revising a middle grade of my own, and it wasn't going well. More precisely, it was going fine, but not great, that sort of revising experience where there's happiness that you're getting closer to finally figuring out the book, and the sadness that you haven't figured the book out yet.

Of course I called Lindsay immediately, because she's someone I talk to about this stuff anyway, and she said something very wise (ugh, of course she did! because she's so good with words!). She said, "Don't forget that I am the best at writing a Lindsay book, and you're the best at writing a Julie book." And then she told me she feels the same thing when she reads particularly great bits in my books. Which was a nice thing to say.

Well, all right. So if I'm the best at writing a Julie book, what does that mean, exactly? What is a Julie book? I've written about this before, but it turns out it's something you have to keep thinking about.

I finally completed an exercise that George Saunders recommended as a way to mine your past. He proposes making a chart of all of the various cultural bits (movies, music, books, people) you were into for five-year chunks of your life, up until now. All of those bits are your influences. They all worked to make you into the person you are now, someone who, say, loves regency dramas but not so much futuristic thrillers. When I was describing this process to my friend Iva, I said "Like, I would put how I was really into Grease when I was 8," and she misheard me and thought I said, "grief." I think we can all agree that someone who was super into Grease at age 8 would likely be a different adult than someone who was, at age 8, super into grief. You can see how all of those various inputs would affect who you are now, and also affect your creative output.

Note that your childhood influences aren't necessarily things you like now. They may not have aged well. Dave and I once tried to push books on our oldest that were highly influential to both of us (oh, all right: Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Still Life with Woodpecker, respectively) and Henry looked through them and declared them both unreadable, which, honestly, they kind of are. But teenager Dave and teenager Julie liked them, and that's important for each of us to note.

So another way to figure this all out is by looking at what lights you up now. These might be recent books/movies/music/ideas you loved, or they could be some of those foundational influences that have stood the test of time. Sometimes, when it's my turn to choose a movie, I get lost in the weeds of trying to pick something that everyone in my family will like (a fairly impossible thing, but it has happened, so I am always trying to strike gold). And when I'm really lost as to what to choose, Ramona always asks me, "Well, what would you pick if it was only for you?" Oh. Right. Me. What are your answers for that? If you pick a book to read, a movie to watch, a song to listen to, that relies only on your sensibility, on what you want, what is it? (Last time Ramona asked me this, we ended up watching Romy and Michelle's High School Reunion, which is a very Julie movie to like, and so I wrote that on my list and mentally noted the joy and silliness, and over-the-top characters who are full of heart that make up that movie.)

I like to think of it this way: all of these influences are like spices, and you on your own are soup, maybe a sort of flavorless potato soup. The soup you eventually become has a lot to do with the spices that are added. You'll end up being soup no matter what, but you might be spicy or cheesy or garlicky. All good, just different.

I recently read the short story The School by Donald Barthelme, and it reminded me so much of my college friend Chris's sense of humor, that I printed it out and gave it to him the next time I saw him, and he said, "Oh, yeah, this is my favorite short story." What are the things about you and what you like that are so solid that someone would read a book or see a movie with those elements and think of you? Or, even better, would read something and know that you must have written it?

The real value of these lists is that you can analyze them in order to quantify the elements you like. The elements you like, presumably, are also the elements that you're putting into the stories you write. (They should be!) So you can look at these lists and see, broadly, plots you tend to love, character types you always go for. You can also get more granular: you like horror, ok, but what kind of horror? Slasher films? Psychological terror? Stories where dolls come alive?

So I look at my chart and see a lot of stories that are silly while being smart. I have a love of madcap and zany. I see stories with strong women. I see I have a real love of a Fish Out of Water plotline. I like characters who are absurd and over-the-top but who are also somehow relatable, and full of heart.

I also see that while I do sometimes get dazzled by plot, the stories and art that have stuck around for me are ones where I fall in love with the characters. Not coincidentally, that's how I approach writing, too. Last summer, I wrote a first draft of a middle grade novel, and I thought I'd save time by plotting it out first. It went terribly. The whole thing was flat and lifeless. While that process might work for others, I learned that it does not work for me. Maybe you can start with a plot and have strong characters arise, but I need to start with characters and have the plot slowly (very slowly, often) come into focus based on what the characters are doing.

This is all part of the lifelong process of getting to know myself as a writer.

I'm fascinated by creative process, how 100 different writers can approach writing 100 different ways, and they all have 100 different charts of influences and lists of favorites. And somehow they all figure out how to make a book. The beauty of this is there's no one right answer. Your influences are your influences. Your process is your process. It's your soup! You might as well take it to the lab and figure out what the ingredients are. (For the record, this process, of doing the charts and stuff, that's the lab. You are the lab. And the soup.)

Thoughts and Links

My writer pal Carter has a new book out, Big and Small and In-Between, illustrated by Daniel Miyares, and it's gorgeous and ingenious and like no other. The New York Times called it "profoundly moving"!

No surprise that this post from Cal Newport resonated with me, about a chemistry Ph.D. student who regained his focus and creativity by leaving his smart phone behind during work hours. Newport says, "This is the question that haunts me: How much genius are we losing to the compulsive need to scroll just a little bit more?"

Thanks to Heidi Fiedler's newsletter, I read this great essay by Annie Barrows about writing from a kid's POV, using Ramona Quimby as an example.

I bought the new Julia Turshen cookbook, and everything I've made has been a winner. Green Spaghetti! Black beans with sofrito! Veggie-packed fried rice! Fish Cakes with potato chips and ricotta! And a couscous and cara cara oranges salad that I am so happy to find in the fridge for lunch. Easy and delicious, all of them.

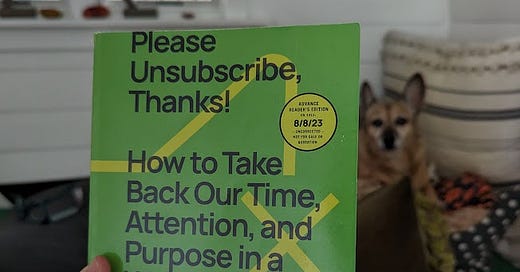

How is my break from social media going? IT'S GREAT. It took a while, but The Feed holds (almost?) no pull for me anymore. Instead of scrolling timelines, I appear to be reading (uh, see the list of books below, and those aren't even all of the ones I read this month). I'm getting a lot more writing done, too.